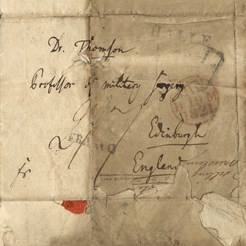

The Meckel Collection, comprising around 8000 anatomical specimens and housed at the University of Halle in Germany, is said to “rank among the largest and most important of its kind in Europe”.(1) This private collection of German anatomist and embryologist Johann Friedrich Meckel the Younger (1781-1833) appears to have had an intriguing history, and in the early 19th century came very close to finding its home at Edinburgh's Surgeons' Hall Museum. Tucked away in a substantial correspondence sequence in the archive at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh lies a bundle of letters sent by the German anatomist to the College, which reveal Meckel actually attempted to sell his entire collection of anatomical preparations to Surgeons’ Hall Museum (the property of RCSEd) in the 1820s.

In fact, the Museum was very keen to purchase the collection of this famed German anatomist. The attempt was aborted however, and the circumstances surrounding the failed sale remain ambiguous, although Meckel's depressive illness (induced by chronic liver disease), together with his stubborn and impulsive personality, may have been a contributing factor. It is evident from the correspondence that an element of defiance against the Prussian state and the ‘academic mediocrity’ prevalent in Halle, drove Meckel to pursue the sale of his beloved human and morbid anatomy collection in Scotland.

Surgeons' Hall

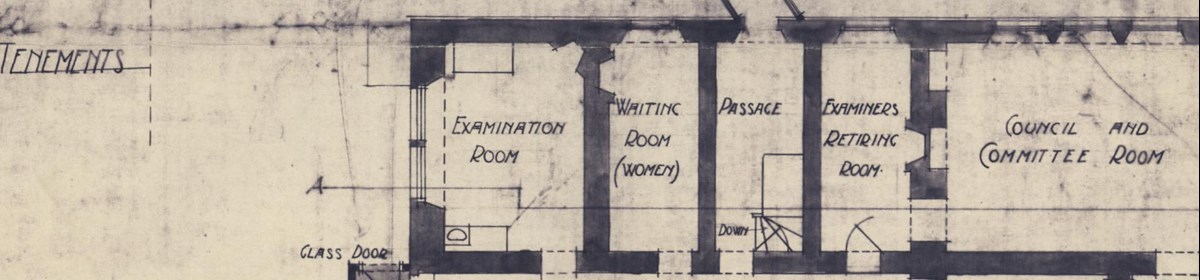

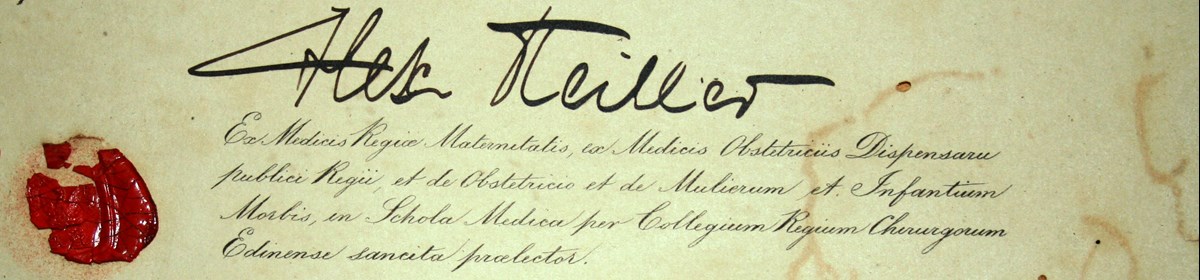

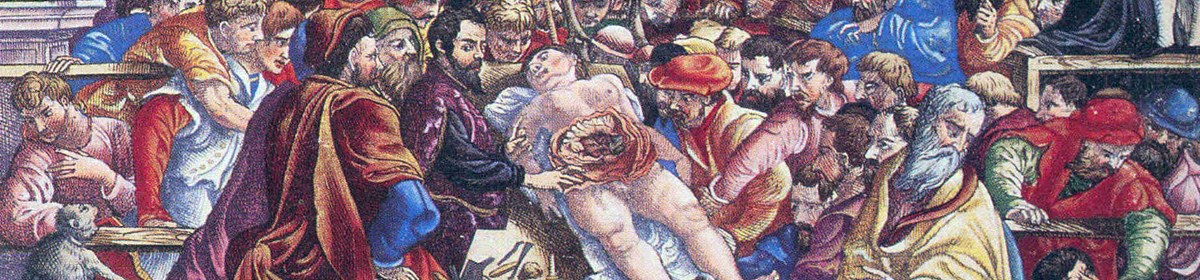

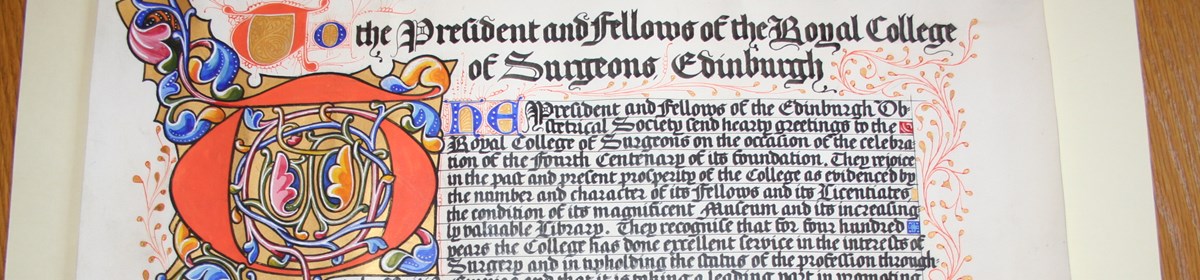

The origins of Surgeons' Hall Museum can be traced to 1699 when the Chirurgeon-Apothacaries announced in the Edinburgh Gazette that they were “making a Collection of all natural and artificiall curiosities”. Daniel Defoe would remark in 1720 on the "Chamber of Rarities … [with] several skeletons of strange creatures, a mummy; and other curious things ”.(2) By 1804, RCSEd Professor of Surgery John Thomson proposed that a museum “of morbid preparation, casts and drawings of diseases” should be more fully established to “facilitate the teaching of surgery”. In 1821 they sought their first serious large-scale purchase, turning their attentions to Meckel, whose collection “was considered to be without a rival in Europe [and] now offered for sale”.(3)

The Anatomical Collection of Johann Friedrich Meckel

Johann Friedrich Meckel was born into a familial medical dynasty comparable to the Bells and Monros in Edinburgh; his father, Philipp Friedrich Theodor Meckel was an anatomist, his grandfather also named Johann Freidrich Meckel (the Elder) was Professor of Anatomy in Berlin, and his brother and nephew were likewise anatomists. It was the youngest son whose skills and observations in comparative and pathological anatomy, and his research on deviations from normal embryonic development have earned him the accolade of one of the greatest anatomists of his time. In 1808, he became Professor of Normal Pathological Anatomy, Surgery and Obstetrics at the University of Halle. Together with his father and grandfather, the Meckels amassed a substantial anatomical and zoological collection, which was housed in the family home and famous in medical and scientific communities; it is said that Napoleon took up residency at the house using it as a temporary base in 1806 when troops occupied Halle. The youngest Meckel spent his lifetime immersed in obtaining specimens and cataloguing his collection. Passing through Germany in the late 1820s, London physician- accoucheur Augustus Granville made a “digression” to “see the University at Halle, and its principal ornament, Meckel, the first and best anatomist of the age”.4 Meckel was delighted to show Granville his preparations and invited him to the family museum, where he found

780 very neat preparations, illustrative of normal anatomy, classed according to structure and functions, which include those intended to exhibit the progress and development of the human foetus…these are followed by all deviations of normal structure…both medical and chirurgical. Of such specimens Meckel’s museum contains not fewer than 2850 and I could not help being forcibly struck by with the great beauty…In part of the museum of comparative anatomy 2500 preparations in spirits, besides some hundreds of dry preparations and skeletons.

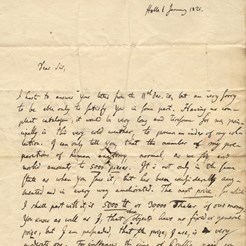

In 1821 Meckel wrote to Surgeons’ Hall about “the number of my preparations of human anatomy, normal, as we shall say, and morbid anatomy amounts to 5000 pieces”. This then was clearly a substantial collection. As Granville remarked, “the family of the Meckels of Halle in Germany had for three generations employed themselves in forming an anatomical museum”. Which begs the question, why did the younger Meckel wish to dispose of the collection “with all my heart…to place it at Edinburgh”, and going by the tone of his letters, with haste? In early 1821, he wrote bitterly to RCSEd:

“If I did not desire earnestly to quit the service, in which I have been treated with the most abominable ingratitude and sacrificed to a parcel of rascals, who inspired by envy and malice, have dared against myself every conceivable villainy”.4

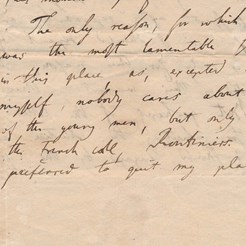

In a later letter he explains,

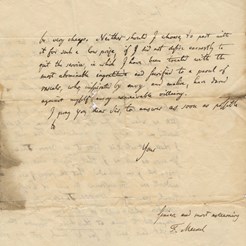

“the only reason, for which I offered my collection, was the most lamentable state of medical instruction in this place, as excepted Prof. Sprengel and perhaps myself, nobody cares about a scientific instruction of the young men…On this account I preferred to quit my place…separating myself from the dearest possession of mine, my collection”.

Granville lamented that “it is to be regretted, that a genius like his [Meckel] should…be wasted or remain useless to science in such a place as Halle, shackled by the toil of an everyday pedagogic instruction”. Prussian administration and the teaching of anatomy’s “elementary principles” irked Meckel, and he was especially frustrated that Halle was treated as provincial and inferior to Berlin. Throughout his communications with Surgeon’s Hall, the German anatomist never wavered in his insistence that the family's prized collection should go to Edinburgh, indeed his letters became increasingly explicit over the following year, seething with animosity against the state and his academic institution. In 1822 he wrote:

“I am forever decided that my collection shall never be sold to the Prussian state in general, nor particularly to this university, and there are already taken measures, that if during my lifetime it might not be sold, neither this state nor the university shall get it in any way after my death”.

After a break in communications, the College, worried, wrote to Meckel to enquire of the delay. However, this appears to be down to Meckel's "very ill state of my health", as he responded,

"I intend by no means to retract the reasons, that engage me to sell my Collection, still persisting in the same degree as before".

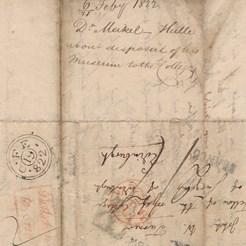

Although negotiations with Edinburgh continued, the sale was aborted, being noted in the RCSEd minutes as being “withdrawn from sale by the family and this College's endeavour came to naught”. It is unclear why this was the case, and is particularly curious given that Meckel was fiercely mistrustful of those around him and adamant his collection would not remain in his hometown. Granville hints to a problem with Meckel's government salary of “1500 rix-thalers as professor, a further sum of 300 rix-thales…for spirits and glass bottles…but he was constantly out of pocket”. However, at some time around the later 1820s (several years after the unsuccessful Edinburgh sale) the Prussian Government “added considerably to his salary”. Following the failure to secure the Meckel pathology collection, Surgeons' Hall acquired the collection of John Barclay, comprising around 2,500 specimens. Around this time the College also acquired the Charles Bell collection from Bell's anatomy school in Great Windmill Street, which was shipped by horse and cart and docked in Leith in 1825. If you have any more information relating to the story behind Meckel's collection we would love to hear from you.

References

(1) Annals of Morphology: Nuchal Cystic Hyrgoma in Five Fetuses from 1819 to 1826.

(2) College Minutes, 5 Oct 1804.

(3) Dawn Kemp, Surgeons' Hall: A Museum Anthology (2009).

(4) Augustus Bozzi Granville, St. Petersburgh, a journal of travels to and from that capital (1829).

Further reading:

Eduard Seidler, Johann Friedrich Meckel the Younger (1781--1833), American Journal of Medical Genetics (1984). The Embryo Project Encyclopaedia, https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/johann-friedrich-meckel-younger-1781-1833.

"I am forever decided that my collection shall never be sold to the Prussian state in general": Johann Friedrich Meckel and Surgeons' Hall Museum

"I am forever decided that my collection shall never be sold to the Prussian state in general": Johann Friedrich Meckel and Surgeons' Hall Museum