‘That each Apprentice who should be convicted of raising or attempting to raise the dead from their graves should forfeit their Freedom, and all privilege competent to them by their indentures and be extruded their Master’s Service’ (Act of the Surgeon Apothecaries, April 17, 1725)

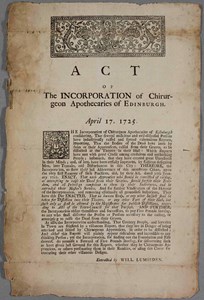

ACT OF THE CHIRURGEON APOTHECARIES OF EDINBURGH, 1725 (RCSED 1/2/1/24)

ACT OF THE CHIRURGEON APOTHECARIES OF EDINBURGH, 1725 (RCSED 1/2/1/24)

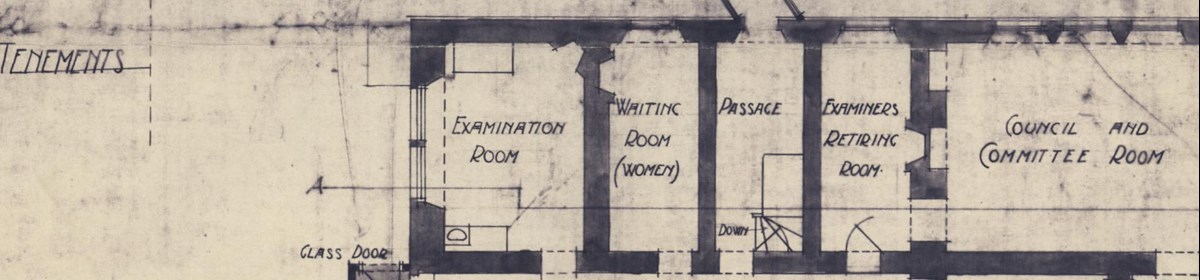

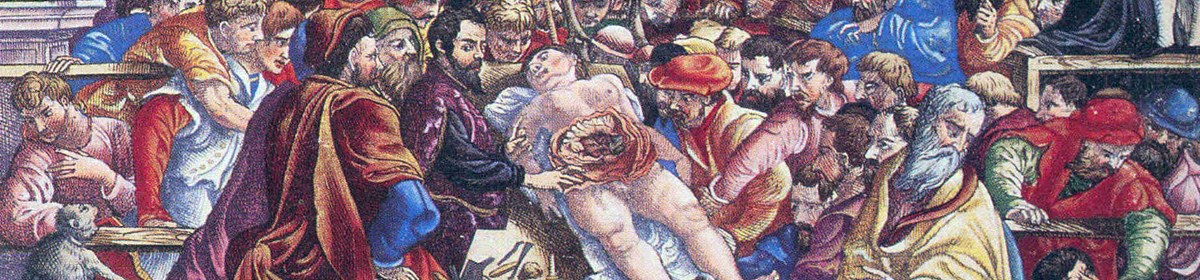

Following “calumnious Reports” and rumours that its members were robbing graves for the purposes of dissection and anatomical research “at the Theatre in their Hall”, the Incorporation of Surgeons were forced to issue a number of acts to “shew their just Abhorrence of this monstrous Crime”. Between 1722 and 1725, no fewer than four notices addressing the reports were issued. The outright banning of grave-robbing by the Incorporation in April 1725 was a further attempt to quash suspicion, accompanied by promises of rewards for the discovery of the crime and the origins of such “villainous Reports”. Curiously, despite the vehemence with which the Incorporation of Surgeons denied accusations of body-snatching, an indenture agreement issued two years later between John Kennedy, chirurgian apothecary burgess of Edinburgh, and apprentice John Bennet makes no reference to such a “monstrous Crime” (RCSEd 5/1/4). Yet, as is known, body snatching by anatomists and medical students did not disappear in Edinburgh, indeed it intensified; in 1771 the Edinburgh surgeons placed an “advertisement in the papers”, offering “a reward [of ten Guineas] to discover who took a dead body out of the Grave”. Recorded in the Incorporation’s minutes (illustrated below), it is likely the surgeons believed the culprit to be one of their own.

A century later the issue of body snatching reached a particularly grim conclusion in Edinburgh after the notorious Burke and Hare murders (and the apparent involvement of anatomist and Surgeons’ Hall conservator and Dr. Robert Knox). In 1832 the Anatomy Act was passed in order to regulate the supply of cadavers to anatomists.

"he shall not be drunk, nor Night-walker, nor a haunter of Debaucht": surgeons’ apprenticeships

By the time the above-mentioned Acts of the 1720s were enforced by the Edinburgh Town Council, 650 apprentices were indentured to members of both the Incorporation of Surgeons and the Society of Barbers (formed in 1722 following the separation of the surgeons and barbers). Surgeons’ apprentices were required to oblige by signing an indenture document, which contained with very particular ethical mandates, especially given that apprentices behaviour appeared to be a cause for “great concern” since the early 1600s. For example, Helen Dingwall notes that by 1612, apprentices were not permitted to wear any “dager, quhinger or knyff (excepting ane knyff to cut their meit wanting the point)”. In 1670, it was reported in the Incorporation’s Minutes that two surgeons were caught brawling on the streets of Edinburgh, and “George Scott foullie transgressit with great oath that he would break his heid”.

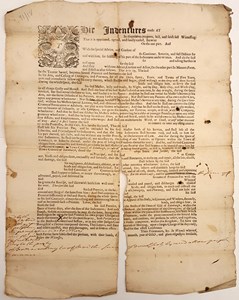

The RCSEd Archive holds a vast collection of apprenticeship indenture records of surgeons, barber surgeons and surgeon apothecaries dating from the late 17th century (ref: RCSEd 5/1), with those of John Bell, Charles Bell (his brother), John Lizars, John Munro and Robert Liston, amongst many other notable names. Included in this section of the Archive is a blank indenture form from 1692. This document starkly illustrates behaviours that the apprentice was forbidden to engage in:

ANNOTATED INDENTURE FORM, 1692 RCSED 5/1/53

ANNOTATED INDENTURE FORM, 1692 RCSED 5/1/53

"And that he shall not reveal his Master’s Secrets in his Arts, nor the secret Diseases of his Patients, to any person whatsoever, nor shall have any Patients of his own under Cure, upon any pretext whatsoever: Nor shall he absent himself from his said Master’s Service at any time, during the space foresaid, without his Master’s special Licence, had, and obtained of him for that effect. And that he shall not commit the filthy Crimes of Fornication or Adultery, nor play at any Games whatsoever; And that he shall not be drunk, nor Night-walker, nor a haunter of Debaucht, or idle Company, nor go to Ale-houses, nor Taverns, to tiple or drink with any Company, whatsoever: And that he shall not disobey his Masters orders, pretending he is elder or younger Prentice, or upon any other pretence whatsoever; And that he keep his ordinar Diets, at Bed and Board, unless he be withdrawn in his Masters necessary Affairs, and Employments, and no otherways: And shall not misbehave be Word, or Deed, or any other manner of way"

Certificates of Moral Character

Helen Dingwall notes how correct behaviour was of “paramount social importance”, with the reputation of the master resting on the behaviour of the apprentice – hence the rather strict nature of the indentures agreement. Despite the excellent literature on the behaviour and responsibilities expected of surgeons’ apprentices during indentureship, what piqued my own curiosity was what happened once the apprenticeship was completed. What did following these strict indenture agreements mean for the future practitioners of the profession? While surveying the Thomas Goldie Scot collection, I discovered a letter written by one James Goldie to his father, John Goldie, dated 16 February 1760.

The letter offers a unique insight into the process of becoming a surgeon’s assistant:

“I shall endeavour to apply myself to My occupation with the utmost care and assiduity, for an opportunity once lost is not so easily regained. I went and entered Myself a Pupil to St Georges Hospital Yesterday, and in about two Months I will be appointed one of the Surgeon assistants to stay in the Hospital. When a person enters into the Hospital, he Must always show to the Board of Directors, a Certificate of his Morals, and good behaviour, while at his apprentiship. [emphasis my own] Which You will please to get from Mr Hill, and let me have it sent as soon as possible, for the Sooner it comes, I will be the Sooner entered into the books which is an advantage”

In Edinburgh, very few surgeons’ apprentices became members of the Incorporation. Of those who succeeded (approximately a quarter), it is probable that they would have received a certificate indicating that they followed the rules of the indenture agreement throughout the apprenticeship.

It is highly likely that the “Mr Hill” referred to in this correspondence is James Hill (1703-1776), who practised in Dumfries (where this branch of the Goldie family were based) and was the husband of Ann McCartney, James Goldie’s first cousin once removed. It is also worth noting that “Father of Edinburgh Surgery” Benjamin Bell (1749 – 1806) was one of James Hill’s sixteen surgical apprentices, and that Hill was well-respected by his peers at the time. For example, as indicated in Ganz’s text, surgeons from as far south as London admired Hill, and even John Bell (1763-1820) held his management of head injuries in high regard. A certificate with his name would have likely carried quite a bit of weight. And evidently, those prone to immoral behaviour need not apply!

There are also several other mentions of the need for a ‘certificate of moral character’ in, for instance, the Medical Times: A Journal of English and Foreign Medicine, and Miscellany of Medical Affairs. In 1844 for example:

- King’s College Aberdeen – a “satisfactory” certificate of moral character required

- University of Glasgow – Every candidate for a medical degree or for surgery must “lodge with the clerk or senate” a “certificate of moral character, by two respectable persons, with evidence having attained the age of 21”

- Royal College of Surgeons of England (Apothecaries’ Hall) – candidates for the certificate of qualification to practise as an apothecary must produce a testimonial of “good moral conduct”; if it comes from the “gentleman, to whom the candidate has been an apprentice, will always be more satisfactory than from any other person”

- Apothecaries Hall, Ireland – produce a document of the indenture of apprenticeship, “bearing the certificate of the licentiate apothecary to whom he has been indentured, that he is of good moral character”

(Hannah Henthorn, RCSEd Archive Volunteer)

Further reading:

- H.M. Dingwall, Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries: Medical Practice in Seventeenth Century Edinburgh, (Tuckwell Press, East Lothian: 1995).

- H.M. Dingwall, A Famous and Flourishing Society: The History of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, 1505-2005, (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: 2005).

- F. MacDonald, Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow, 1599-1858: The History of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow, Volume 1, (1999).

- J.C. Ganz, ‘James Hill of Dumfries (1703–1776): A Surgeon of Excellence’, Archives of Neuroscience, at http://archneurosci.com/33435.pdf (2014).

Surgeons’ Apprentices: Bodysnatching and other Immoral Behaviour in 18th-Century Edinburgh

Surgeons’ Apprentices: Bodysnatching and other Immoral Behaviour in 18th-Century Edinburgh