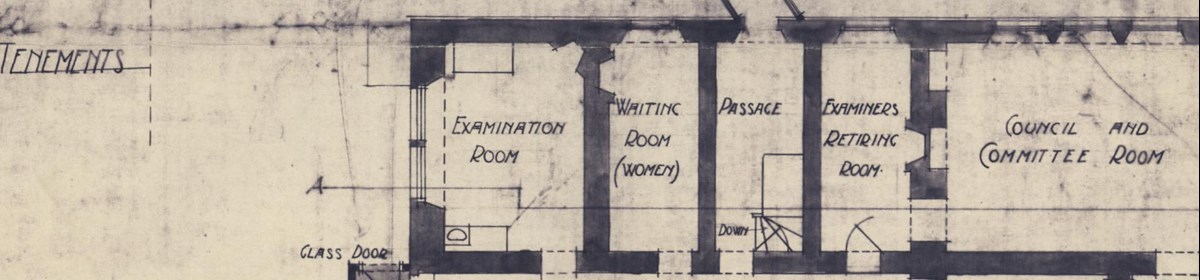

Headquarters of the School of Medicine at Surgeons’ Hall (adjacent to Playfair building at RCSEd)

Headquarters of the School of Medicine at Surgeons’ Hall (adjacent to Playfair building at RCSEd)

To mark Holocaust Memorial Day, this post will highlight stories from the archive of refugee medical students who either had, or were attempting to flee Nazi Europe, and who sought to obtain qualification from Edinburgh and Glasgow’s Royal Colleges in order to practice in Britain. In the Dean of the School, they found a man who was willing to challenge the British medical establishment who were increasingly closing ranks against foreign exiles.

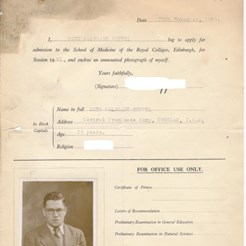

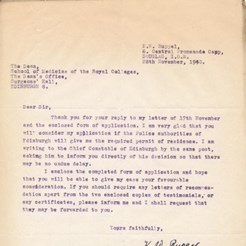

In November 1938, John Orr, Dean of the School of Medicine of the Scottish Royal Colleges (based at Surgeons’ Hall, Edinburgh) received a letter from Giorgio Szymanski, a refugee of Polish origin. Szymanski was writing to confirm his completion of “one year’s Clinical Surgery at the Hospital S. Orsola of the University of Bologna” where “I have been a Medical Student for five years”. He also confirmed he had the necessary finances to undertake extra-mural medical education in Edinburgh in order to qualify to practice in Britain . The letter sits at the top of a file of correspondence in the School of Medicine Archive, and on first appearances is a seemingly routine application to the Triple Qualification (TQ) Committee on Admissions. However, the remaining file on Szymanski reveals a complex and moving personal story. Writing in September of that year from Italy, in response to Orr’s acceptance of his application, Szymanski alluded to the “many difficulties I overcame”.

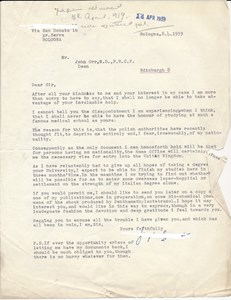

Final letter from Giorgio Szymanski to John Orr, 1939 (SOM 5/2/3/5)

Final letter from Giorgio Szymanski to John Orr, 1939 (SOM 5/2/3/5)

Born in St. Petersburg, Szymanski’s mother “left Russia with me and my younger brother because of the Communist Revolution”, to live temporarily in Danzig, thereafter moving to Berlin. Szymanski matriculated from school in 1933, however, “after the accession to power of the Nazi Government I could not study at a German University”. He subsequently went to Italy “whose attitude then was a friendly one [towards émigré Jews]”, and matriculated at the University of Bologna. Yet, in August 1938 regulations came into force prohibiting foreigners to continue their studies in Italy. He then looked to Scotland to take his final examinations, where he found a sympathetic ear in John Orr. The student encountered yet another obstacle however, and in November 1939, he wrote to Orr,

“after all your kindness to me and your interest in my case I am more than sorry to say, that I shall no longer be able to take advantage of your invaluable help. The reason for this is, that the Polish authorities have recently thought fit to deprive me entirely and, I fear, irrevocably of my nationality”.

Without official “nationality”, the British Home Office had refused to grant the necessary visa for Szymanski’s entry to Britain. Consequently, the student’s only hope, he felt, was to “find out whether it will be possible to enter some overseas leper-hospital or settlement on the strength of my Italian degree”.

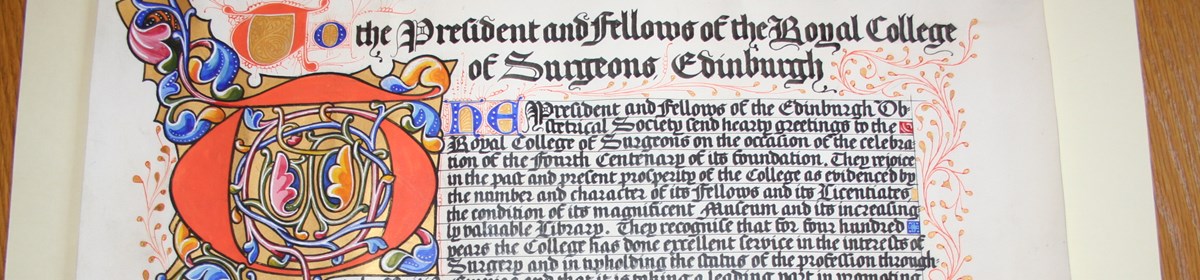

The Triple Qualification of the Scottish Royal Medical Colleges

The TQ Diploma was first offered in 1884 by the three Scottish Royal Medical Colleges; Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd), Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (RCPE), and the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (FPSG, later RCPSG). As an alternative to the University M.D., the TQ survived until 1993, with its longevity owing much to its flexibility in accommodating a diverse range of candidates. For instance, in its early days, this route to qualification was particularly emancipating for women, whose gender denied them matriculation at any Scottish university until 1892.

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1937. School of Medicine students undertook clinical training here

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1937. School of Medicine students undertook clinical training here

In addition, the Colleges particularly welcomed doctors from overseas who wished to study in Edinburgh or Glasgow in order to qualify on the TQ Register with the General Medical Council (GMC), and therefore be licensed to practice in Britain. Foreign students came to Scotland for varied reasons, although often, they sought escape from racial discrimination or war in their home country, which the sample group in this blog is concerned. It is the case that medical migrants and exiles from Central Europe faced widespread anti-alien hostility from the British medical establishment, who perceived them as a threat to national security. Yet the Archive of the School of Medicine of the Scottish Royal Colleges offers an alternative – more compassionate – story.

Surgeons’ Hall was the administrative base of the School of Medicine as well as the TQ, and as such, the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh hold a vast collection of archives of the School, TQ examinations and its candidates. (You can read about the School of Medicine Archive here). A particular highlight of this collection is the inclusion of over 1000 student files from the 1930 and 40s, which contain application forms with portrait photographs, letters of recommendation, candidate examination records and background correspondence (and are relatively untapped by researchers). A significant number of applicants came from students of foreign nationality, including many Europeans fleeing the perilous measures imposed by Hitler. While some students wrote to the Dean from London after escaping Europe, as many corresponded from their home country. Like Szymanski’s file, this archive offers a window into the lived experience of medical refugees, from the repression they encountered in their homeland and also the hostile wartime restrictions they faced in Britain while attempting to obtain a medical license. The files also highlight how medical refugees found a friendly and helping hand in the Dean of the School, John Orr, and with Scotland’s regulations being less stringent than those of English licensing bodies (in terms of the period of clinical study required), the Scottish extra-mural schools proved to offer hope and a lifeline to medical refugees.

Medical refugees in the archive

As evidenced throughout the collection, Giorgio Szymanski’s experience was typical for a large number of medical students looking to Scotland as a safe haven that also allowed them to study. Helen Dingwall has calculated that between 1933 and 1938, “nearly 25% of successful candidates were of European Jewish origin”.1 A number of “non-Aryan Christians” also made up the profile of European applicants during this period. For some successful candidates, it is possible to trace their subsequent educational career once in Scotland. Yet, sadly for many like Szymanski who applied yet were unable to come to Britain, we can only ponder their fate.

In 1938 the Women’s Work Department of the Methodist Missionary Society, based in London, wrote to Orr of 31 year old Dr. Margarete Hildebrand, “a German woman doctor at present resident in Switzerland…[who was] virtually expelled from Germany because of Jewish blood”. While the doctor at this time held a position in “a clinique in Berne, Switzerland will no longer allow her to practice there…she has to leave Switzerland and has nowhere to go”. As such, Hildebrand was seeking to secure a British qualification in Edinburgh or Glasgow. Orr’s hands were however tied by the TQ quota system; in 1939 for example, ninety foreign graduates were on a session waiting list for seven places for overseas students at Surgeons’ Hall. Yet Orr’s genuine empathy and compassion is evident. He wrote back to the Missionary Society to “assure you of my deep sympathy with those unfortunate people and of my regret that personally I cannot assist them as fully as I should like”.

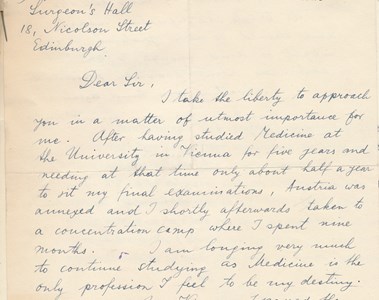

Some letters in the archive make for quite difficult reading. In 1939, the year following German annexation (Anschluss), three Austrian men in their twenties wrote a joint letter to Orr, explaining that “we were unfortunately kept prisoners of the Gestapo, at the Concentration Camps of Dachau and Buchenwalde for nearly a year…we are anxious to resume our studies in Scotland”. And in 1940 a student from the University of Vienna wrote: “After having studied Medicine at the University of Vienna for five years…Austria was annexed and I shortly afterwards taken to a concentration camp where I spent nine months". Unfortunately, while Orr noted that in Scotland “concessions are given to students of foreign universities”, the duration of his previous study fell short of the required length necessary for admission. While it is unclear of this Austrian student’s fate he appears to have escaped to London.

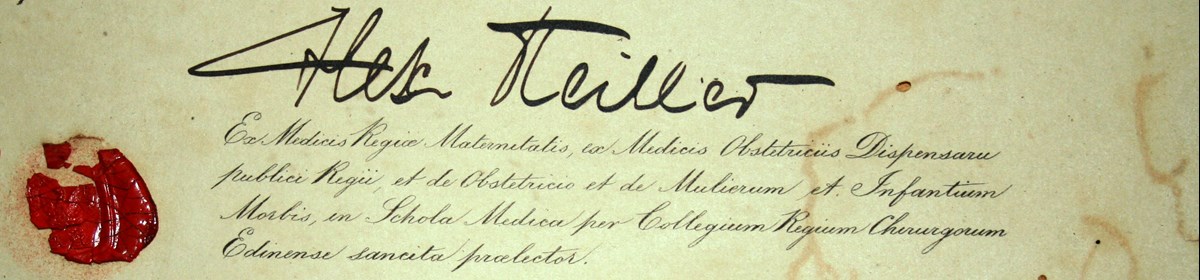

Dr. John Orr, Dean of the School of Medicine of the Royal Colleges (1924-49)

The student files also provide some insight into the lives of medical refugees once in Scotland. While John Orr was constrained by administrative regulations re the quota system, his empathetic character is evident throughout the files; “her position is a very cruel one” he wrote, in response to an application by a Czech refugee. In addition to his attempts to accommodate as many medical refugees as he could in their applications to the Royal Colleges, his support continued of successful applicants during their studies in Edinburgh or Glasgow.

During this period, the British Medical Association increasingly sought to control the numbers of foreign students entering the country, leading to what one historian has called “entrenched hostility” to medical exiles.2 It is argued the BMA even “manipulated the Home Office policies” in order to restrict the education, employment and movement of medical refugees in Britain. Corresponding with Orr in November 1940, one German national wrote, “Before my interment as a technical enemy alien (I am a refugee of Nazi oppression) I was pursuing a course of medical studies the University of Sheffield”. However, owing to “local restriction forbidding all aliens of enemy status to enter the university and hospitals there”, the student therefore looked to Edinburgh where Orr was “happy to consider his application”. Orr pointed out though, that as a protected area, the student would require “permission from the police to enter the area”.

In order to prevent the leakage of information “through aliens resident in the neighbourhood”, in April 1940 the British Home Office announced an amendment to the Alien Order, 1920. This had the effect that aliens of enemy nationality were forbidden to live in “protected areas”, including the Firth of Forth. This therefore had an impact on students at the School of Medicine in Edinburgh. In June 1940, a rather desperate German woman wrote to Orr from Glasgow concerning her husband, a student at the School of Medicine, who was “fetched by two detectives, with many other refugees…He is going to be sent away tomorrow and I do not know where”. A leading European expert in rheumatic and nervous diseases with a Spa practice in Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen), her husband had previously in his home country “lost his position and medical practice and property” before fleeing to Britain and seeking to take a medical qualification in Edinburgh. She was appealing to Orr to apply to the Home Office to free the doctor in order for him to sit his exams. Orr made the appeal, and consequently, the Edinburgh Chief Constable wrote to the couple that “I have carefully considered your case and decided to grant you permission to visit Edinburgh daily…for the purpose of sitting your examination”. However, the doctor was not permitted to reside in Edinburgh, and was ordered to return to Glasgow in the evenings, which lay outside the “protected areas”. Happily, we hold other records of the doctor in a separate collection at RCSEd, which confirms he passed the Triple Qualification Examination in 1941 and also shows his full course schedule during his time in Scotland.

While the Dean explicitly acknowledged deference to police orders, at times it appeared to frustrate him. Interestingly, Orr made an appeal for compassion in the Glasgow Herald in May 1940 regarding the “check on all aliens between 16 and 60 living in the Eastern areas of Scotland” which included “80-100 enemy subjects…arrested and interned” in Edinburgh. Below this report is a “Plea for Medical Students” to the Chief Constable from “Dr. John Orr, Dean of the School of Medicine of the Royal Colleges” regarding the group of refugee doctors who had “come to Edinburgh to study for a medical qualification”. The internment of these medical students, Orr announced, “would mean a serious position for them because most of them were men with limited resources”. In response to a student threatened with evacuation from Edinburgh in 1941, the Dean wrote, “I am always ready to be of assistance where possible in these very sad cases”.

The Scottish Royal Medical Colleges indeed garnered a widespread reputation of ‘tolerance’. Conversely, the Scottish Universities were reluctant to deviate from the “current climate of opinion in Britain and felt that it would be unwise to provide special facilities for the admission of foreign students”.3 Additionally, a number of international organisations appear to have taken umbrage to John Orr’s ‘open’ policies, with many letters revealing explicit anti-semitic prejudice prevalent in American medical schools, for instance. A student writing to Orr in 1938 claimed,

“I just received notice from the New York State Education Department that (in furtherance of their Machiavellian scheme in conjunction with the AMA) they will no longer recognize your school as proper preparation from New York candidates…it seems that you were too tolerant of Jews and allowed them to study in your school when this democratic country wanted them limited in numbers”.

Two years earlier, John Orr wrote of a potential candidate, “I believe Mr Dunn would do well as a student in the school of medicine in this country [Scotland] where he is likely to enjoy a little more freedom in carrying on his studies than he is in an American school”.

The archive of the Scottish Royal Medical Colleges illustrates how a group of medical refugees looked to Scotland as a way to escape persecution in Hitler’s Europe, while also continuing with their careers through extra mural study and British qualification. You can view the archive containing these student applications to the School of Medicine of the Royal Colleges in our catalogue here (ref: SOM). TQ candidate examination registers and full course schedules can be found in our main institutional archive (ref: RCSEd 6).

- Helen Dingwall, ‘The Triple Qualification Examination of the Scottish Medical and Surgical Colleges’, Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 40 (2010).

- Paul Weindling, ‘Medical Refugees and the Modernisation of British Medicine 1930-1960’, Social History of Medicine, 22 (2009).

- Kenneth Collins, ‘European Refugee Physicians in Scotland’, Social History of Medicine, 22 (2009).

“I am a refugee of Nazi oppression”: The Scottish Royal Medical Colleges and Medical Refugees

“I am a refugee of Nazi oppression”: The Scottish Royal Medical Colleges and Medical Refugees