Our guest blog post is from Marieke Hendriksen, a postdoctoral researcher at Utrecht University. Marieke will be joining us in October here at the RCSEd Library and Archive on a Wellcome Trust Research Bursary. Her research is a study on practices and resources used by the members of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, to preserve and make models of the human body in the period 1700-1850. Look out for related events and future blogs!

The art of modelling [in plaster] trenches upon that of the artist, and, as everyone knows, is practiced by a number of persons as an art. Professors of this branch of science are in every large city, and I recommend to do as I did, viz. visit the studio of the artificer in stucco. All in this line in Edinburgh, at least, I found most communicative, and happy at all times to explain everything, and much more of the art than the anatomist can possibly ever require. I candidly confess that twenty volumes would not have given me the insight of one hour’s sojourn in the garret room of my Italian friend. Frederick John Knox, The Anatomist’s Instructor, Edinburgh 1836

Frederick Knox was a surgeon and conservator of the museum at Old Surgeon’s Hall in Edinburgh, and the brother of Robert Knox, conservator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, whom he assisted in dissections for years. In his book The Anatomist’s Instructor and Museum Companion: being practical Directions for the Formation and subsequent Management of Anatomical Museums he listed not only techniques for making anatomical preparations, but also included sections on drawing and plaster casting. Knox called modeling with plaster of Paris a very useful art for anatomists as the material was easy to obtain, and very suitable for making casts and models for the anatomical museum or the anatomist’s personal collection. As the above quote shows, Knox learned plaster casting techniques from artists in Edinburgh, and although he included some practical guidelines in his book, he advised other anatomists to do the same.

Title Page of Frederick .J. Knox’s Anatomist’s Instructor, 1836

Title Page of Frederick .J. Knox’s Anatomist’s Instructor, 1836

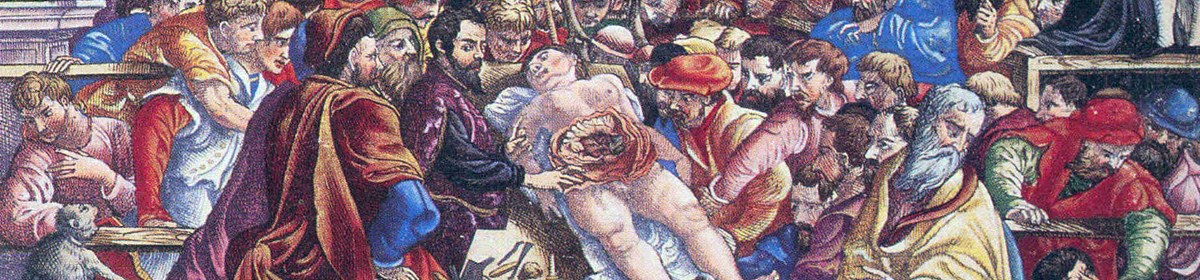

It has long been known that medical men and visual artists worked closely together in the production of anatomical atlases and models in early modern Europe, and that anatomists and other medical men learned drawing techniques to illustrate their own work, yet we know little about the development, understanding and transmission of various other techniques for depicting the body among artists and anatomists. My research within the ERC ARTECHNE project at Utrecht university aims to fill that gap by focusing on the development and mutual exchange of techniques like plaster casting, corrosion, colouring, and wax and papier-mâché modeling by artists and anatomists. The practices and resources used by the members of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh to preserve and make models of the human body in the period 1700-1850 form a fascinating case study for this research project. Recently I was awarded a grant by the Wellcome Trust to go to Edinburgh for two months and use the RCSEd Institutional Archive, which has been catalogued and preserved through a Wellcome Trust Research Resources Grant, as a starting point.

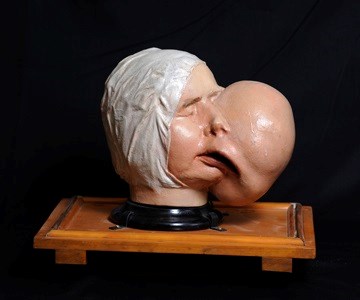

Plaster Model of the Head and Face Showing Deformity Produced by a Large Fibroma of the Left, 1837. Surgeons’ Hall Museums, RCSEd

Plaster Model of the Head and Face Showing Deformity Produced by a Large Fibroma of the Left, 1837. Surgeons’ Hall Museums, RCSEd

We do know that medical practitioners and artists were working together at the College in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, and that surgeons and anatomists used anatomical drawings as teaching and research aids.(1) Yet a number of questions has remained unanswered thus far. What were the networks of association between artists, surgeons and anatomists? More specifically, how did medical practitioners teach each other techniques for preservation and modeling of the human body? Did Edinburgh anatomists and physicians take or organize classes to learn artistic techniques that could be used to create anatomical preparations and models, or did they consult artistic or anatomical handbooks? Were recipes and manuals copied, instructions given in writing or in person? Are there any distinct differences from or similarities with practices elsewhere? From mid-October until mid-December 2016, I will try to answer these and other questions using the archives and collections at RCSEd, supported by Archive, Library and Museum staff.

(1) Berkowitz, Carin. Charles Bell and the Anatomy of Reform. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Preserving and modelling the body: technique in anatomical practice and visual arts at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, 1700-1850

Preserving and modelling the body: technique in anatomical practice and visual arts at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, 1700-1850