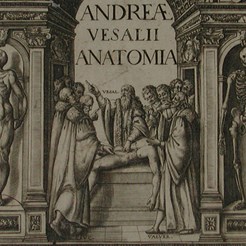

We’ve been greatly enjoying the BBC4 series The Beauty of Anatomy, examining the relationship between anatomical discoveries and works of art that illustrate them, which has prompted us to explore some of our own anatomical atlases collection. Presented by Dr. Adam Rutherford, last week’s episode featured Belgian anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius (1514-64), whose most influential work, the dissection-based De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) was first published in 1543. Vesalius has been credited as the ‘Founder of Modern Anatomy’, with his work signifying the first accurate human anatomical atlas. His work also represents one of the earliest serious challenges to the Galenic orthodoxy in the description of the human body (Galen’s dissections had been carried out on animals, not man).

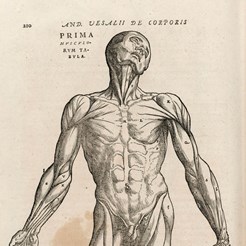

For Vesalius, the impetus behind Fabrica was his wish to better engage his students and provide images illustrating anatomy, in a way that was both innovative and memorable. Yet, the end result went further than that, with his work ushering in a new European anatomical tradition based on observation, with Fabrica becoming the benchmark in anatomical illustration for hundreds of years. During this episode of The Beauty of Anatomy, Rutherford visits the Wellcome Library to view a spectacular first edition of Fabrica. In the library at RCSEd we hold editions of Fabrica from 1604 and 1725, and we have been admiring some of these striking ‘muscle men’ and ‘living skeleton’ figures, from Fabrica and other works.

As pointed out by Rutherford, Vesaillus became the most famous anatomist in Europe with his anatomical drawings copied and plagiarised throughout Europe.

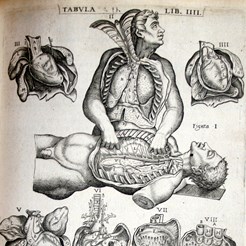

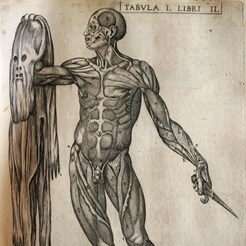

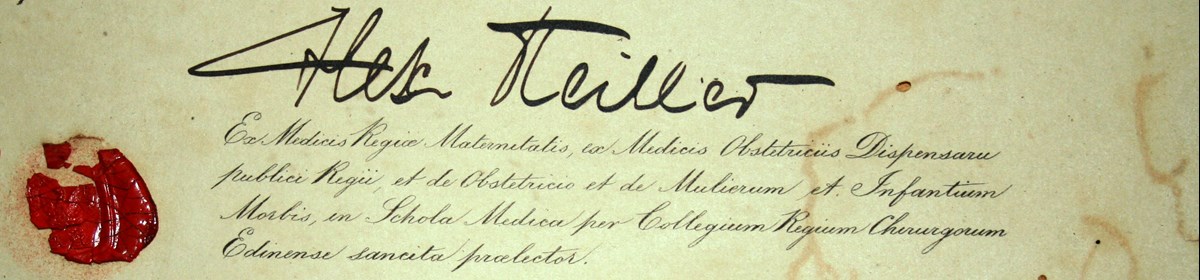

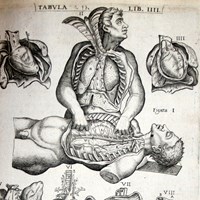

Juan Valverde de Amusco (1525-1588) was one such individual criticized for borrowing heavily from Fabrica. Valverde was a Spanish physician who trained under Versalius, and he “was explicit in his admiration for Vesalius’s achievement”.[1] The anatomical plates illustrated below are taken from our beautiful 1579 Plantin edition of his Vivae imagines partium corporis humani aereis formos expressae. This edition was a re-engraved suite of the plates from Valverde’s highly influential anatomical work Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano. First published in Rome in 1556, this work was largely based on the Vesalius woodcuts for Fabrica.

While Vesalius himself criticized Valverde for his lack of experience in practical dissection the text however was penned solely by Valverde. He also made some improvements on Vesalius’ anatomical observations and introduced 15 new woodcuts of his own, including the famous image of the flayed man holding aloft his own skin, which may have been informed by Michelangelo’s flayed skin in the Sistine Chapel. Valverde’s compendium became “one of the most read anatomic-related documents in the sixteenth century”. [2] The work of the renaissance anatomists marked both a new age and long period of surgical developments.

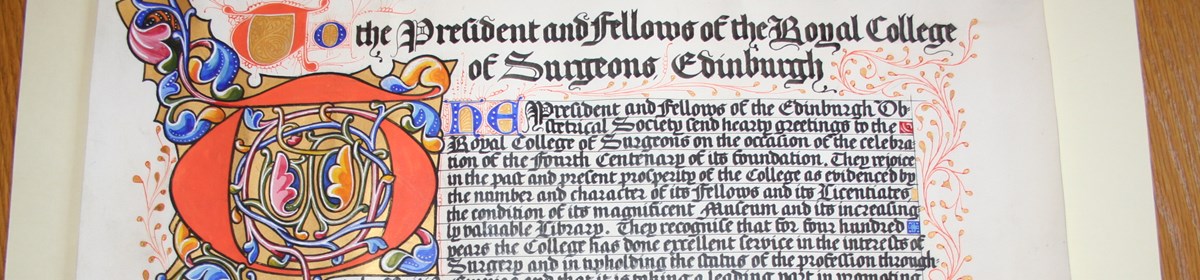

At the RCSEd Library and Archive we have around 1600 books on anatomy and anatomists, which are of regular interest to our membership, medical historians and art students.

Further reading:

For a discussion of Valverde’s relationship with Vesalius, see Meyer and Wirt, ‘The Amuscan Illustrations’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 14 (1943), 667-89).

[1] Imaging the Renaissance Body, Edinburgh University Library/Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, http://www.arsanatomica.lib.ed.ac.uk/valverde.html

[2] A. Lopez-Valverde, R. Gomez de Diego, J. De Vicente, ‘Oral anatomy in the sixteenth century: Juan Valverde de Amusco’, British Dental Journal, 215, 141 – 143 (2013)

The Beauty of Anatomy

The Beauty of Anatomy